Crowd Control

"We will meet, and there we may rehearse most obscenely and courageously. Take pains. Be perfect. Adieu." —William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

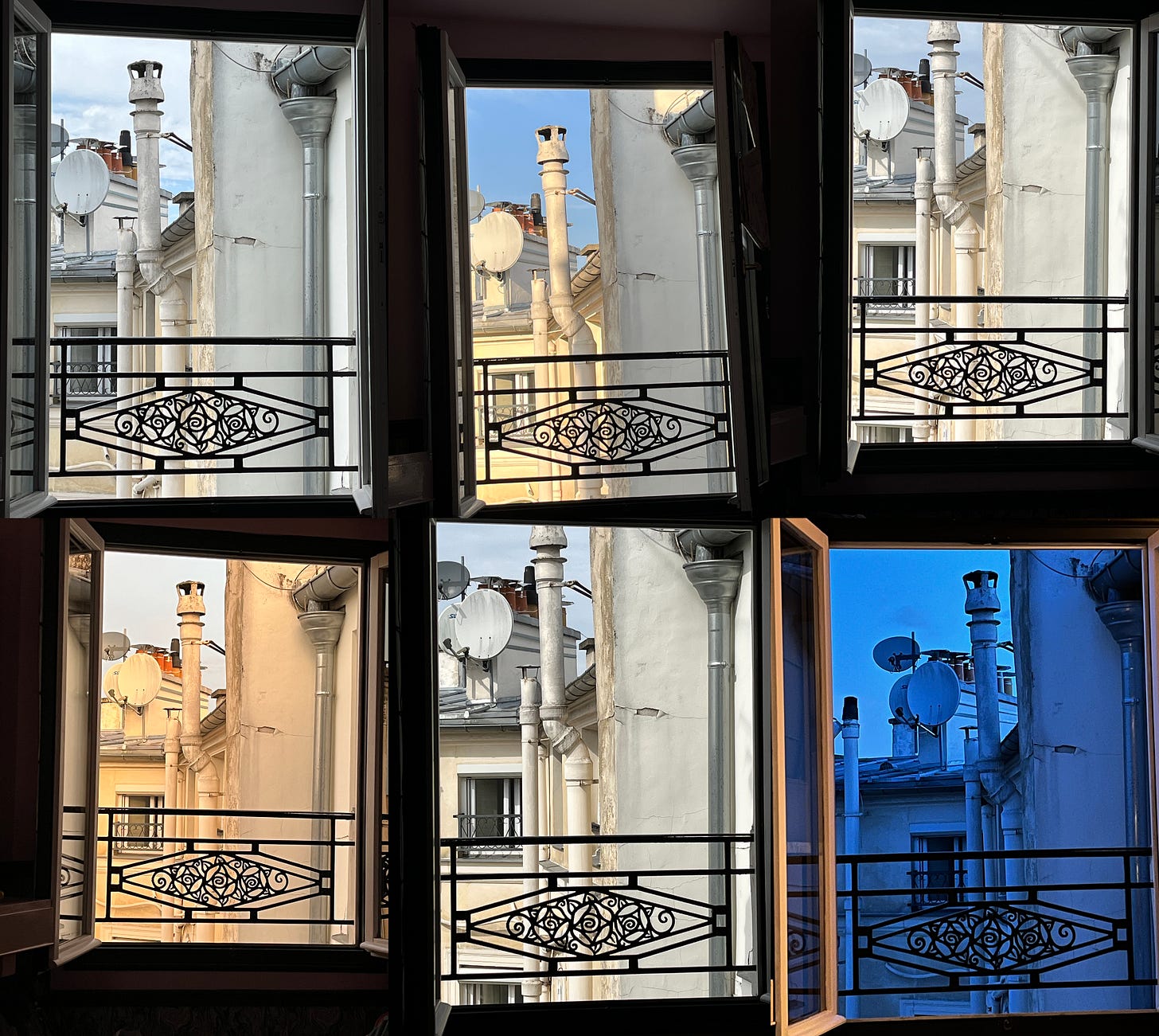

As my meanderings through the streets, pubs, cafes, bookstores, cemeteries, and museums of Dublin, London, Paris, Strasbourg, and Berlin fall into their waning yet dreamy final phases, each iteration having blessed my soul with all the restorative serenity afforded anyone able to separate themselves, at least for a time, from the disintegrating American empire crackling with despair and enraged by its precipitous – yet wholly avoidable! – fall into fascism, as if rage were a navigable wing and not a mindless stone, I find myself preparing my cartoonist’s pen for its furious return to the United States where every line that I draw will, once again, become a homing beacon for all who wish me harm and yearn to delegitimize my voice as if I was yodeling nonsense and demanding a precise echo from all within earshot.

Admittedly, expressing contempt for nefarious men and women who despise all who refuse to recognize their nefariousness as virtue has been going on for a very, very long time, meaning one should never consider the impulse to ridicule those most deserving of contempt in a world made wonkishly unjust by hierarchy’s need to slot us all into segregated currencies to be unique, though the techniques by artists, poets, and provocateurs of all sorts have certainly shifted over time, both in public expression and private.

In fact, the earliest known example of a caricature explicitly drawn to ridicule a specific authority figure is Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s 1676 drawing of Pope Innocent XI. Like other cartoons doodled into the margins of his letters, this was a drawing that Bernini never intended for public circulation much less for consideration by Pope Innocent XI himself, who, though he frequently expressed open hostility toward the arts and commissioned fewer works than his predecessors, was still the artist’s primary patron. The caricature depicts the Bishop of Rome, who was rumored to be a notorious hypochondriac, as a reclusive shut-in either giving a blessing or issuing a papal decree from his bed, his enormous mitre extending off his head like the abdomen of an engorged insect, his frail neck a pathetic twig, his wee hand a puny and spooky claw. Certainly, when compared to the caricatures masterfully drawn by Annibale Carracci and his brother Agostino nearly a hundred years earlier, or those by Leonardo da Vinci a hundred years before that, Bernini’s drawing of the Pope seems amateurish at best. Still, it is the very first satire targeting a particular individual of tremendous social stature, which is of greater significance than a question of aesthetics—plus it is a satire that never would’ve been realized had Bernini not had the camaraderie of like-minded friends guaranteed to appreciate the parody and sure to get the joke, an important fact that reinforces the notion that of equal importance to an artist’s ability to create a piece of art is having an audience for which it can resonate, even if it is just a private one.

Of course, Bernini produced his artwork during the pre-modern era in Europe when the parameters that determined what a true artist was were determined by fixed canons of beauty and a narrow set of purely academic guidelines devised to prevent a painter or a sculptor or an engraver from expressing a uniquely subjective opinion about anything of a personal nature. For hundreds of years, it was the job of the artist to demonstrate how technically proficient he was at rendering putti, distressed drapery, animate skulls, horses, manicured landscapes, and the idealized human form in campy, overly dramatic poses and almost always within the context of clichéd Christian, Greek, and Roman mythologies. Indeed, there were artists who occasionally drifted into territory one might regard as a deviation from the worship of the classical form—specifically, the allegorical genre paintings of peasants by Pieter Bruegel (the Elder and Younger), the borderline science fiction fantasy works of Hieronymus Bosch, the fruit portraits of Giuseppe Arcimboldo, the crudely nightmarish engravings of Hans Beham—yet these examples still reflect strict adherence to the rigid techniques of draftsmanship demanded by what would eventually formally coalesce into the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

As a result, Bernini’s caricature of Pope Innocent XI, because it wasn’t considered legitimate art at the time of its creation, was likely interpreted as the equivalent of a snarky note passed around in the back row of a classroom when the teacher wasn’t looking, its effect on the world limited to a brief snicker from a miniscule number of people who might’ve glanced at it surreptitiously for somewhere between 6 and 11 seconds. Indeed, it wasn’t until the concept of romanticism and avant-gardism—both of which began in earnest as a revolt against intransigent church doctrine, academicism, and the political and cultural demands of the aristocracy in the late 1700s with the canvases of Goya, Géricault, and Delacroix and the savagely irreverent cartoons of British satirists James Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson, and George Cruikshank—that artists were finally able to recognize the true power and potential of the poison in their pens and, specifically, how caricaturing and anti-establishmentarianism had value as forms of creative expression.

Thus was born the steady succession of reciprocal art movements most familiar to us: Impressionism, Fauvism, Expressionism, Cubism, Futurism, Dadaism, Surrealism, Social Realism, Minimalism, Deconstructivism, Conceptualism, and so on. Each movement found momentum in its desire to claim distinction from all previous incarnations while at the same time competing simultaneously with all other existing philosophies, each hoping to claim top recognition for innovation and originality and relevance to the here and now.

Essential to the perpetuation and cohesion of these groups was the willingness of the participants to synchronize the typography of their visual alphabet and to announce their mutual disdain for the same conventional elements that they wished to trivialize within the dominant culture. Most important was their belief that artists had every right to enthusiastically criticize whatever political system or religious ideology they interpreted as retarding the spiritual, psychological, and intellectual evolution of the human race, nationalities, ethnicities, and denominations notwithstanding. No longer were autocrats to be considered the leading authority on autocracy any more than the Vatican was to be the sole administrator of moral law. For the first time, those either victimized or marginalized by power would have a seat at the table—having crashed the party!—from where to voice an opinion about social justice, truth, beauty, absurdity, ecstasy, and indifference.

Simultaneous with the deliberate innovations and rigorous contempt for superstition and blind allegiance to the noblesse ushered in by the Age of Enlightenment, the arts community, like the scientific and philosophical communities, adopted reason and individualism as the central strategy for how best to deduce meaning and purpose from life. Ironically, for the concept of individualism to have any relevance in the world, it first needed to be appropriated by a collective of nonconformists; that is, a cohesive organization convened to demonstrate a coordinated front against conformity and to formalize what only made sense as an informal and innate and uncensored behavior. Peter Bürger explained this phenomenon in his 1974 book, Theory of the Avant-Garde, as follows: “It is art as an institution which determines the measure of political effect avant-garde works can have and which determines that art in bourgeois society continues to be a realm distinct from the praxis of life. Art as an institution neutralizes the political content of the individual work. It prevents the contents of works that press for radical change in a society—the abolition of alienation—from having any practical effect.”

Crucial, then, to the ability of the artist to motivate his or her audience into experiencing kinship with the progressive, agitator mentality of the painter, satirist, or cartoonist who was either embedded in a particular school of art or associated with a distinct genre was to allow that connection with whatever collective he or she was identified with to resonate as camaraderie instead of something that had been artificially summoned in order to satisfy some broad theoretical conceit. To echo Oscar Wilde, who so famously found pretension in social structures unforgivable, “Oh, I hate the cheap severity of abstract ethics!”

Because longevity eventually degrades radicalism into complacency, most art movements were intended to self-destruct after a few years, the repetition of a rendering technique or a theory of functionality ultimately producing monotony, and monotony sooner or later breeding the dogma and automated thinking that the art movement was originally concocted to ameliorate. Paramount to the integrity of any art form, after all, is an awareness of when the purpose for creating the work is no longer obvious or the strategy for combating the myopia and priggishness that the modern art movement detests has failed to effect positive change.

That said, let’s not make the mistake of thinking that the impulse to ridicule those most deserving of contempt in a world made wonkishly unjust by hierarchy’s need to slot us all into segregated currencies no longer has purpose because the techniqies with which we’re most familiar have been rendered passé through the unfortunate failue to prevent the emergence of our current dystopia.

In that particular circumstance, the impulse, because of its dire imperative, will be the very thing to determine the means by which we express our dismay.

Get to work Fish!

I'd forgotten the word 'putti.' Odd, since they're probably the very essence of a pedophile's wet dream, and to be sure, these are the muggery buggery days of pedos ruling the world.

Your deep knowledge of art history and unique take on the aesthetic and anesthetic tides and currents that shape it is awesome (couldn't think of a more erudite or hackneyed term to use there, HA!).

Welcome back to Circle VIII of hell on Earth, Fish! IX is coming -- but the planet has to burn to ash and dust before evil is locked ice-tight from the waist down in the next Glacial Age. Everyone forgets that dry ice is actually an agonizing burn.

These days, in these interstitial times, that marrow-deep quickening is an acute ex nihilo in nihilum (from nothing to nothing) sense of being and presence ... reminding me again of Kerouac's epiphany in DESOLATION PEAK, as Paul Maher, Jr. recounts in "Prelude to Big Sur" ....

=== https://acrossanunderwood.wordpress.com/2016/10/08/prelude-to-big-sur/ ===

He recalled his Desolation Peak satori: “I don’t know, I don’t care, and it doesn’t make any difference.” It didn’t even make a difference to go to Heaven, or the work it took to get there. There is no connection to what we are doing now and what we’ll be doing in Heaven. On earth, there is no “honest justice” so one is forced to hang in the balance in the great Void existing between Heaven and Earth.

Death haunted, Kerouac pictured his gravestone and its epitaph:

I DON’T KNOW

I DON’T CARE

AND IT DOESN’T MAKE

ANY DIFFERENCE

Kerouac daydreamed of his death, of dying alone in the whirling Void, of the futility of a vainglorious funeral. He feels wiser because he sees the humor of it all. It wasn’t the death of Self that brings you closer to Heaven, but the “not-Self.”

==================